This is a linkpost for Ryan Beck's winning essay in Metaculus's Szilard Fortified Essay Contest. Essays focused on questions pertaining to long-term nuclear risks and called for authors to support their arguments with quantified forecasts.

Readers are encouraged to click through to the original essay where they can engage directly with the author and make their own forecasts.

Heightened geopolitical tensions can increase the risk of war, and when tensions between nuclear powers deteriorate the risk of nuclear war can increase. One such relationship facing heightened tensions is between the United States and China. This is particularly concerning as China has recently increased its nuclear stockpile and shown increased aggression toward neighboring states. This essay examines the risk of nuclear war between the US and China and offers possible means of lowering that risk.

Background

China's nuclear stockpile growth has been notable, increasing by 60 warheads from 2019 to 2020, the largest recent increase of any nuclear capable state (see the figure below from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), US and Russia not shown).

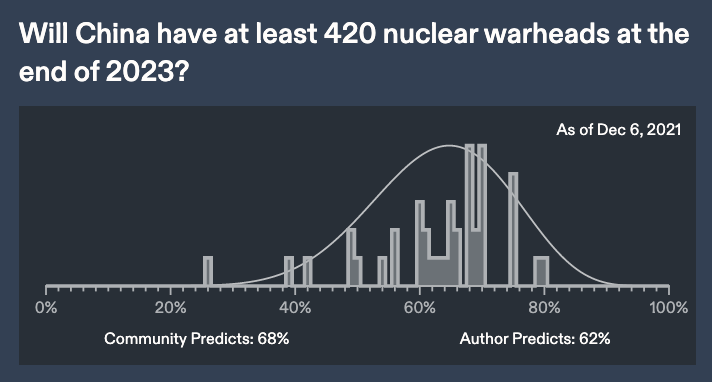

Additionally, a report by the Pentagon estimates that China could expand to 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030. As of December 6th the Metaculus community forecasts a 68% chance that China will have at least 420 nuclear weapons prior to 2024.

This is significant not only due to the proliferation of nuclear weapons, but also due to China's geopolitical situation. China has seen worsening relations with the US, as well as with neighboring countries such as Taiwan, Japan, and India. These worsening relations combined with the growth in China's nuclear stockpile could indicate an increased risk of nuclear war involving China.

The Risk

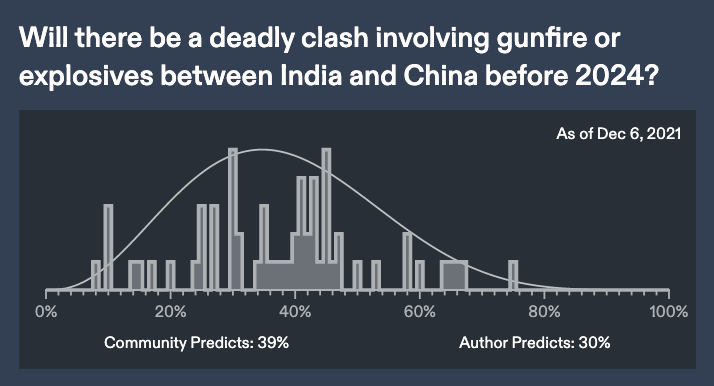

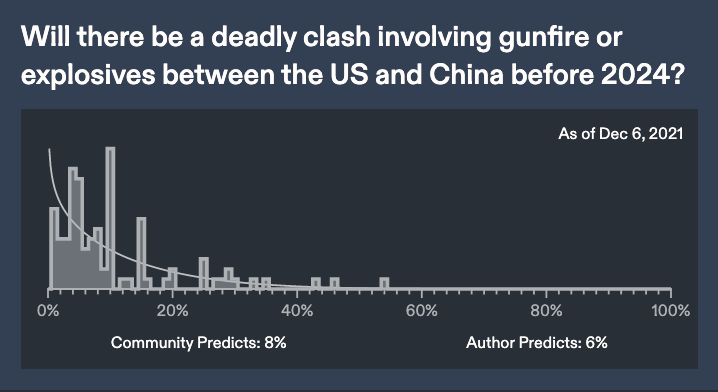

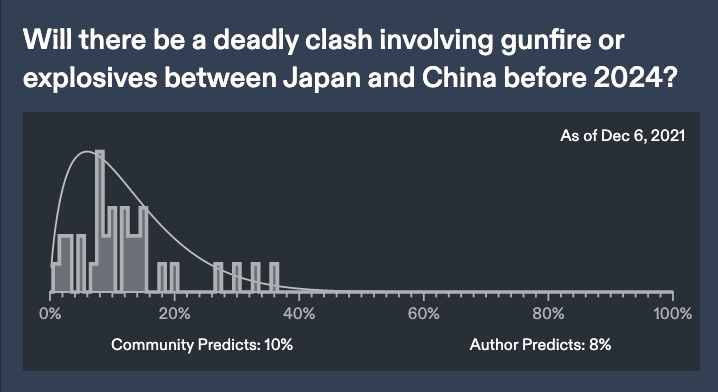

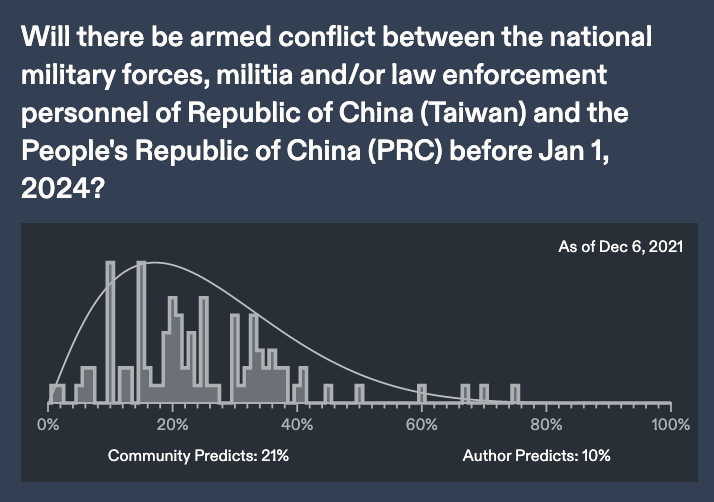

A nuclear conflict may not start as an outright offensive. A small scale clash, even one sparked by accident or misunderstanding, could quickly escalate. Below are the Metaculus community forecasts for a deadly armed conflict happening prior to 2024 between China and the states China appears to be at heightened tensions with.

The community sees the largest risk of a clash with India, followed by Taiwan, Japan, and then the US. Notably the community places the probability of a clash with India at 39% and with Taiwan at 21%. These are forecasts for a ~2 year period. If those probabilities were to be sustained in the long term it would suggest over a 90% chance of a deadly clash with India in the next 10 years and over 90% chance of a clash with Taiwan in the next 20 years. However, it's likely that the community doesn't consider these probabilities to be perpetual, instead reflecting a current period of heightened tensions.

The Role of the US

The community forecasts an 8% chance of a deadly clash involving gunfire or explosives between the US and China by 2024, the lowest of any of the other countries so far mentioned. So why focus on the US? I have two main reasons. One is that the US is tied to varying degrees to India, Taiwan, and Japan, which means that conflict between China and any of these countries would pose a significant risk of drawing the US into direct conflict with China. The second reason is that this nuclear risk discussion is happening in a Western context and stakeholders are more likely to be able to influence policy in the US than other countries of interest.

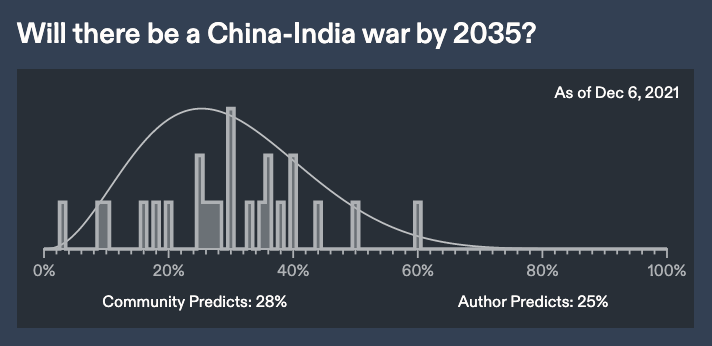

While the latter reason is fairly self-explanatory, the former needs elaboration. Of the countries at risk of conflict with China mentioned above, only the US and India have nuclear weapons. The community forecasts a significant chance of deadly armed conflict between China and India by 2024, but many of these possible scenarios would not lead to a full scale war but instead may consist of isolated border clashes. As evidence that this is the case, compare the community forecast for this question involving a China-India war by 2035. The probability is significantly lower than would be implied by extrapolating out from the deadly clash question.

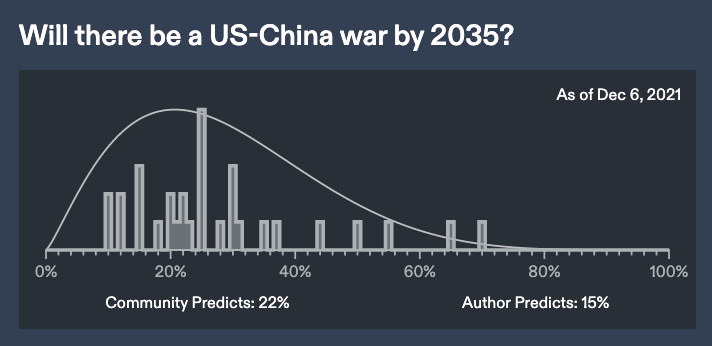

Additionally, when compared to the probability of war between the US and China by 2035, the difference between the community forecasts for these questions is only 6%, compared to a 31% difference in the forecasts for the deadly clash questions.

Japan and Taiwan have similar considerations due to their proximity to China. A deadly clash between these countries can occur for many reasons that may not result in full blown war, such as naval or aerial encounters in the straits between their countries.

In my view the risk of war between the US and China depends greatly on its relationships with India, Taiwan, and Japan. The US has a mutual defense treaty with Japan, has continued to develop its relationship with Taiwan and may defend it if attacked, and has been improving its relationship with India. If any of these countries enter into war with China, the chances of US involvement are significant.

Improving Relations by Ending the Trade War

The US has little ability to foster improved diplomatic relations between China and China's neighbors as its own relations with China are largely negative. Improving relations with China would not only provide the US with greater ability to foster diplomacy between these countries and China, but would also slightly raise the chances that a crisis or incident occurring between the two superpowers would be handled diplomatically. In my opinion the best avenue for improving US-China relations is by ending the trade war.

The US-China trade war began in 2018 when President Donald Trump raised tariffs on China. The intent was to put pressure on China to make changes to its trade practices, but several years have passed and tariffs are still at extreme levels; President Joe Biden has maintained tariffs on China and shows no sign of reducing them. This is despite the fact that most economists believe the burden of US tariffs imposed on China fall on US citizens and that imposing new tariffs does not improve Americans' welfare. Additionally, studies suggest that the tariffs result in a very large annual cost per job created.

In my view this is one of the biggest areas where the US could significantly improve its relationship with China with very little downside. There is significant room here for the US to take the first step on reducing tariffs, which could deescalate high tensions in this area of the US-China relationship. Reducing tariffs without demanding concessions from China could be a win-win; it eliminates an ineffective and costly policy and could improve relations with China. The main downsides are political. The US may not want to appear weak, reducing tariffs could damage the political standing of the executive with the industries protected by these tariffs, and it means giving up the leverage intended to be gained by imposing the tariffs. But these political costs could be reduced by communicating to the public the evidence showing tariffs are ineffective, and whatever leverage may exist has so far failed to produce meaningful improvements in trade status for the US.

Limited Alternatives

I think the trade war is the best option for improving diplomacy because other US-China issues are more complex and have less room for meaningful shifts. Below is a brief overview of some of the biggest points of contention and why they're more complex.

- Taiwan: US-Taiwan relations have grown in recent years, which has caused China to react with aggressive displays. There is little room for improvement here, as China-Taiwan relations have a long history, and the US must walk a fine line between supporting Taiwan but also not signaling to Taiwan that US support will enable Taiwan to declare full independence, which could raise the likelihood of hostilities from China.

- Uyghurs and Hong Kong: The treatment of the Uyghurs in China and China's oppressive actions toward Hong Kong have led to condemnation from the international community, including the US. This is an area where the US is unlikely to back down, and it should not back down as support for human rights is important.

- General Diplomacy: Limitations on journalists, closing of consulates, semiconductor technology disagreements, revocation of student visas, Olympics diplomatic boycott, and more. There is potential here for improvement in relations, but the breakdown in relations has been broad and is often tied to the other difficult issues mentioned in this section.

While there isn't much room to improve relations in these areas, it's possible that the positive effect on relations caused by ending the trade war could open up more opportunities for improved relations.

Conclusion

The US and China face a significant risk of conflict due not only to the negative relationship between them, but also due to the negative relationship between China and its neighbors, including countries to which the US has made commitments of support and, in the case of Japan, defense. The Metaculus community has forecast the risk of war between the US and China to be 22% by 2035, which should concern everyone interested in preventing nuclear warfare. To reduce this risk, efforts should be made to improve the relationship between the US and China without the US sacrificing its support for human rights and for its allies. One potential means of accomplishing this could be by ending the trade war, a solution which has significant upsides for the US and manageable domestic political risks.

One point about the Pentagon figure, they said "700 warheads by 2027 and at least 1000 by 2030"[1]. Meaning most likely over 1k. I actually made a bet that they will revise the estimate up again in this/next year's report, e.g. this year we may see "900-1000 by 2027 and 1200-1500 by 2030". They said the stockpile was only expected to double over the decade to the ~400s in the 2020 report to Congress, so by increasing estimates more gradually they're probably mitigating a loss of face & hard questions over the massive intelligence failure. Signs point to China simply seeking parity with the US/Rus (~1500 deployed), I don't see why they'd expand only to 1000 and stop there.

Comments by DoD people support this hypothesis[2]. Common sense tells us this too: Even if the ~300 new DF-41 silos discovered last year are each armed with only 3 warheads (the missile can carry ~10 max), and no other silos are built/discovered, that's still 900 warheads on top of the ~400 already in service. China's nuclear force has traditionally been mobile-based, and TEL (truck)/rail[3]-basing are probably expanding similarly; silos are just the most visible. (Plus, submarines.)

I know a lot of ways to reduce China-US nuclear risk even without non-starters to the pro-democracy crowd (e.g. giving up defence commitments to certain US allies). There seems to be some major civilizational inadequacy in this area; i.e. obvious ways to have a major reduction on the risk that just nobody's bothered to implement. I don't think economic tensions/trade wars are very relevant to nuclear risk compared to more important factors in the grand scheme of things to be frank.

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF ↩︎

https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-will-soon-surpass-russia-nuclear-threat-senior-us-military-official-2021-08-27/ ↩︎

https://www.stratcom.mil/Portals/8/Documents/2022 USSTRATCOM Posture Statement.pdf?ver=CUIoOCLyos9xe9C9I0XjMQ%3D%3D ↩︎

I'm not well-versed in this area but reading through the Chinese nuclear notebook from November 2021 they seem kind of skeptical of claims like this and point out that China could also be intending the silos to be a "shell game". Quoting from the notebook:

Would you disagree with that assessment?

I agree that the trade war issue is probably low impact, but I focused on it because it has few downsides and potential upsides for nuclear risk. What ways to reduce China-US nuclear risk do you suggest? From what I've seen so far (which is admittedly very little) it seems like there are very few feasible options to reduce nuclear risk with China, and most available options involve a lot of unknowns with regard to implementation and effectiveness and potentially have significant downsides.

Really enjoyed the way forecasts were integrated into the essay. Seems like a really useful approach!

I broadly agree that ending the trade war would be good. I'm not sure it's as easy to mitigate the political downsides as you suggest, though. I think it's quite unlikely that "these political costs could be reduced by communicating to the public the evidence showing tariffs are ineffective". Mostly because it's difficult to explain such a complicated issue on which people's intuitions point the other way. But also because it would be a political act and you'd have half the politicians in the country spreading the opposite message.

One longer-term scenario I'd have some credence in is: if Biden were to follow through on this action, I'd expect it to have a negative effect on his chances for re-election (maybe make it 1-5% less likely?), and any increase in the chance of Biden losing the next election could be worse for US-China relations than the gain from ending the trade war (something like 50% confidence).

I'm also not sure it's true that "other US-China issues are more complex and have less room for meaningful shifts". This seems to neglect the fact that the US and China have mostly managed to continue cooperating on climate change negotiations even though relations on the whole have remained frosty. I'd be a fan of trying to find other issues of common ground, even if they're less important than bilateral trade or territorial issues. For example, perhaps they could coordinate on space governance, clean tech investment, arms control, and maybe foreign aid?

I think cooperation on issues of lesser importance can be helpful as they allow countries the chance to show they can agree and uphold agreements, build trust, build personal ties between elites and diplomats, and reduce misunderstandings and misconceptions of the other side's intentions.

Your comment is 3 months old, but somehow I missed it back when I was posted and am just now seeing it, so I just wanted to say these are all good points, particularly about cooperation on other issues like your climate example!

Regarding ending the trade war, what is your more general stance on such measures? Do you think that Russia shouldn't have been sanctioned, or that the sanctions should have been milder? Similarly, do you think that the US should refrain from sanctions if, e.g. China threatens or invades Taiwan?

I guess in all of those cases, you could make the case that trade restrictions increase tensions and thereby indirectly the risk of a nuclear war. But you could also argue that such restrictions are net positive, through various effects. Also, you could of course argue that there are relevant differences between the three cases.

Overall my sense is that it's pretty difficult to work out the net effect of sanctions and other trade restrictions.

That's a good question, I've thought about this some before and while it's kind of messy I think the general gist of my thoughts is something like this (framed from a US perspective but I think it generalizes to most countries):

So my rough framework isn't that we should always avoid tariffs and sanctions, but that they should be limited, targeted to serve a purpose, and be in conjunction with our allies where possible. I think sanctions on China over the treatment of Uyghurs are justified and from what I've heard these have been targeted at the Xinjiang region and at Chinese entities involved.

Similarly, the Russian invasion warrants severe consequences, and sanctions are more effective here because they've been imposed in conjunction with allies. If China were to invade Taiwan or threaten to do so a similar response would be justified.

The big difference to me with the trade war was that it was based on a misguided attempt to fix our trade imbalance, which my impression is that most economists don't really see as a problem. The idea also seemed to be to use tariffs as a bargaining chip to negotiate better trade practices such as IP protection. But these tariffs were applied unilaterally and don't appear to be targeted at all, and never seemed likely to accomplish these goals. And in the meantime they've made things more expensive for Americans and have probably damaged relations with China with nothing to show for it.

Thanks for the response. Yeah I agree that starting a trade war over trade imbalances is significantly different from initiating human rights-motivated sanctions.

You mention ending the trade war as the main mechanism by which we could ease US-China tensions. I agree that this policy change seems especially tractable, but it does not appear to me to be an effective means of avoiding a global conflict. As Stefan Schubert pointed out, the tariffs appear to have a very modest effect on either the American or Chinese economy.

The elephant in the room, as you alluded to, is Taiwan. A Chinese invasion of Taiwan, and subsequent intervention by the United States, is plausibly the most likely trigger for World War 3 in the near-term future. You write that,

However, we can just as easily say that because the US position on Taiwan is ambiguous, there is much more room for improvement here. More specifically, since it's unclear how and whether the US will intervene in a Chinese-Taiwan conflict, this indicates that US foreign policy is variable and easily subject to change.

In this situation, we can imagine that a mere change in attitude from the US president could be enough to dramatically influence the plausibility of a global conflict. For instance, suppose in the future, an anti-Taiwan president gets elected in America, and as a result, China decides to invade Taiwan, confident that the US will not respond. This election would then have profound implications for not only Taiwan, but the shape of global politics going forward.

We need to think very seriously about how the US should approach the China-Taiwan situation. Should we attempt to defend a vibrant democracy at the risk of starting a catastrophic nuclear war? This is a real question, with real stakes, and one where public opinion has a real chance of determining what ends up happening. In my opinion, the trade war is much less important.

This is a good point, I completely agree that the trade war is of small importance relative to things like relations with Taiwan. My reason for focusing on the trade war though is because trade deescalation would have very few downsides and would probably be a substantial positive all on its own before even considering the potential positive effects it could have on relations with China and possibly nuclear risk.

To me the same can't be said for the Taiwan issue. The optimal policy here is far from clear to me. Strategic ambiguity is our intentional policy, and I'm not sure clarifying our stance would be preferable to that. Committing to defend Taiwan could allow Taiwan to do more provocative things, which could lead to war. Declaring we will not defend Taiwan could empower China to invade. I agree it's a significant issue that should be carefully considered, but it's also an issue that I'm sure international relations experts have spilled huge amounts of ink over so I'm not sure if there are any clearly superior policy improvements available in this area.

I agree. I think we're both on the same page about the merits of ending the trade war, as an issue by itself.

Right. From my perspective, this is what makes focusing on Taiwan precisely right thing to do in a high-level analysis.

My understanding of your point here is something like, "The US-Taiwan policy is a super complicated issue so I decided not to even touch it." But, since the US-Taiwan policy is also the most important question regarding US-China relations, not talking about it is basically just avoiding the hard part of the issue. It's going to be difficult to make any progress if we don't do the hard work of actually addressing the central problem.

(Maybe this is an unfair analogy, but I find what you're saying to be a bit similar to, "I have an essay due in 12 hours. It's on an extremely fraught topic, and I'm unsure whether my thesis is sound, or whether the supporting arguments make any sense. So, rather than deeply reconsider the points I make in my essay, I'll just focus on making sure the essay has the right formatting instead." I can sympathize with this sort of procrastination emotionally, but the clock is still ticking.)

I expect experts to have basically spilled a huge amount of ink about every policy regarding US-China relations, so I don't see this as a uniquely asymmetric argument against thinking about Taiwan. Maybe your point is merely that these experts have not yet come to a conclusion, so it seems unlikely that you could come to a conclusion in the span of a short essay. This would be fair reply, but I have two brief heuristic thoughts on that,

To be clear I'm not arguing that people shouldn't think about it or try to solve it. I'm definitely in favor of more discussion on that topic and I'd love to read some high effort analysis from an EA perspective.

If I'm understanding correctly the main point you're making is that I probably shouldn't have said this:

Which in that case that's a fair critique. I'm not well-informed enough to know the options here and their advantages and risks in great detail, so my perception that there's not much room for improvement could be way off base.

I'd summarize my position as having the perception that the Taiwan issue is a hard question that I'm not equipped to solve and I'm skeptical that there are significant improvements available there, so instead I focused on a topic that I view as low hanging fruit. Though I was probably wrong to characterize the Taiwan issue as futile or unimprovable, instead I should have characterized it as a highly complex issue that I'm not equipped to do justice to and I perceive as having substantial downsides to any shift in policy.

Thanks for the continued discussion.

I think I'm making two points. The first point was, yeah, I think there is substantial room for improvement here. But the second point is necessary: analyzing the situation with Taiwan is crucial if we seek to effectively reduce nuclear risk.

I do not think it was wrong to focus on the trade war. It depends on your goals. If you wanted to promote quick, actionable and robust advice, it made sense. If you wanted to stare straight into the abyss, and solve the problem directly, it made a little less sense. Sometimes the first thing is what we need. But, as I'm glad to hear, you seem to agree with me that we also sometimes need to do the second thing.

Yeah definitely on the same page then! I agree with what you said there with the possible exception or caveat that I'm skeptical on improvements to the Taiwan issue and that if you find or know of any persuasive abyss-staring arguments on this topic (or write them yourself) I'd appreciate it if you share them with me because I'd be happy to be wrong in my skepticism and would like to learn more about any promising options.

This refers to a 2019 survey. It would be good to have more recent data, and more direct evidence.

I don't know this area at all, but here is data from one review paper I found.

Another method finds that:

Asking about China tariffs in 2019 seems like it the sort of extremely partisan topic that the typically very good IGM can struggle with. I wonder if the answer might be different if the question was instead asked today, as now that Biden has endorsed Trump's strategy the partisan valence may have changed.

Agree. And not just because it was initiated by Trump, but because of a general aversion to such policies.

I didn't have access to your link but I found another version of it here.

To be honest I'm not familiar with the direct evidence either so I'm mostly relying on secondhand impressions and general descriptions of tariff burdens falling on consumers. I searched around briefly just now and found this paper (also cited in the paper you linked as Amiti et al. (2020b)) which reports:

However it's not clear to me what the relationship is between tariff burden and the welfare loss estimates you mentioned in your comment. It seems to me like they could be measuring different things.

Thanks. Tbc I don't have a strong view on the object-level issue. I just thought it would be good to have more evidence than that early survey.

That makes sense, I agree it's better to have more direct sources.