Mo Putera

Bio

Participation4

CE Research Training Program graduate and research contractor at ARMoR under the Global Impact Placements program, working on cost-benefit analyses to help combat AMR. Currently exploring roles involving research distillation and quantitative analysis to improve decision-making e.g. applied prioritization research, previously supported by a FTX Future Fund regrant and later Open Philanthropy's affected grantees program. Previously spent 6 years doing data analytics, business intelligence and knowledge + project management in various industries (airlines, e-commerce) and departments (commercial, marketing), after majoring in physics at UCLA. Also collaborating on a local charity evaluation initiative with the moonshot aim of reorienting Malaysia's giving landscape towards effectiveness.

I first learned about effective altruism circa 2014 via A Modest Proposal, a polemic on using dead children as units of currency to force readers to grapple with the opportunity costs of subpar resource allocation under triage. I have never stopped thinking about it since, although my relationship to it has changed quite a bit; I related to Tyler's personal story (which unsurprisingly also references A Modest Proposal as a life-changing polemic):

I thought my own story might be more relatable for friends with a history of devotion – unusual people who’ve found themselves dedicating their lives to a particular moral vision, whether it was (or is) Buddhism, Christianity, social justice, or climate activism. When these visions gobble up all other meaning in the life of their devotees, well, that sucks. I go through my own history of devotion to effective altruism. It’s the story of [wanting to help] turning into [needing to help] turning into [living to help] turning into [wanting to die] turning into [wanting to help again, because helping is part of a rich life].

Posts 3

Comments116

Topic contributions3

From Richard Y Chappell's post Theory-Driven Applied Ethics, answering "what is there for the applied ethicist to do, that could be philosophically interesting?", emphasis mine:

A better option may be to appeal to mid-level principles likely to be shared by a wide range of moral theories. Indeed, I think much of the best work in applied ethics can be understood along these lines. The mid-level principles may be supported by vivid thought experiments (e.g. Thomson’s violinist, or Singer’s pond), but these hypothetical scenarios are taken to be practically illuminating precisely because they support mid-level principles (supporting bodily autonomy, or duties of beneficence) that we can then apply generally, including to real-life cases.

The feasibility of this principled approach to applied ethics creates an opening for a valuable (non-trivial) form of theory-driven applied ethics. Indeed, I think Singer’s famous argument is a perfect example of this. For while Singer in no way assumes utilitarianism in his famous argument for duties of beneficence, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the originator of this argument was a utilitarian. Different moral theories shape our moral perspectives in ways that make different factors more or less salient to us. (Beneficence is much more central to utilitarianism, even if other theories ought to be on board with it too.)

So one fruitful way to do theory-driven applied ethics is to think about what important moral insights tend to be overlooked by conventional morality. That was basically my approach to pandemic ethics: to those who think along broadly utilitarian lines, it’s predictable that people are going to be way too reluctant to approve superficially “risky” actions (like variolation or challenge trials) even when inaction would be riskier. And when these interventions are entirely voluntary—and the alternative of exposure to greater status quo risks is not—you can construct powerful theory-neutral arguments in their favour. These arguments don’t need to assume utilitarianism. Still, it’s not a coincidence that a utilitarian would notice the problem and come up with such arguments.

Another form of theory-driven applied ethics is to just do normative ethics directed at confused applied ethicists. For example, it’s commonplace for people to object that medical resource allocation that seeks to maximize quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) is “objectionably discriminatory” against the elderly and disabled, as a matter of principle. But, as I argue in my paper, Against 'Saving Lives': Equal Concern and Differential Impact, this objection is deeply confused. There is nothing “objectionably discriminatory” about preferring to bestow 50 extra life-years to one person over a mere 5 life-years to another. The former is a vastly greater benefit, and if we are to count everyone equally, we should always prefer greater benefits over lesser ones. It’s in fact the opposing view, which treats all life-saving interventions as equal, which fails to give equal weight to the interests of those who have so much more at stake.

Two asides:

- This seems broadly correct (at least for someone who shares my biases); e.g. even in pure math John von Neumann warned:

As a mathematical discipline travels far from its empirical source, or still more, if it is a second and third generation only indirectly inspired by ideas coming from "reality" it is beset with very grave dangers. It becomes more and more purely aestheticizing, more and more purely l'art pour l'art. This need not be bad, if the field is surrounded by correlated subjects, which still have closer empirical connections, or if the discipline is under the influence of men with an exceptionally well-developed taste. But there is a grave danger that the subject will develop along the line of least resistance, that the stream, so far from its source, will separate into a multitude of insignificant branches, and that the discipline will become a disorganized mass of details and complexities. In other words, at a great distance from its empirical source, or after much "abstract" inbreeding, a mathematical subject is in danger of degeneration. ... In any event, whenever this stage is reached, the only remedy seems to me to be the rejuvenating return to the source: the re-injection of more or less directly empirical ideas.

- This makes me wonder if it would be fruitful to look at & somehow incorporate mid-level principles into decision-relevant cost-effectiveness analyses that attempt to incorporate moral uncertainty, e.g. HLI's app or Rethink's CCM. (This is not at all a fleshed-out thought, to be clear)

There have been some previous attempts, e.g. EA Philippines’ Local Charity Effectiveness Research and Tentative List of Recommended Charities (list here) and the EA Malaysia Cause Prioritisation Report (2021) (see also the local priorities research tag for more).

It's also (understandably) quite hard to get charities to share sensitive financial information re: room for more funding considerations, especially if you're not e.g. a large funder.

The following is a collection of long quotes from Ozy Brennan's post On John Woolman (which I stumbled upon via Aaron Gertler) that spoke to me. Woolman was clearly what David Chapman would call mission-oriented with respect to meaning of and purpose in life; Chapman argues instead for what he calls "enjoyable usefulness", which is I think healthier in ~every way ... it just doesn't resonate. All bolded text is my own emphasis, not Ozy's.

As a child, Woolman experienced a moment of moral awakening: ... [anecdote]

This anecdote epitomizes the two driving forces of John Woolman’s personality: deep compassion and the refusal to ever cut himself a moment of slack. You might say “it was just a bird”; you might say “come on, Woolman, what were you? Ten?” Woolman never thought like that. It was wrong to kill; he had killed; that was all there was to say about it.

When Woolman was a teenager, the general feeling among Quakers was that they were soft, self-indulgent, not like the strong and courageous Quakers of previous generations, unlikely to run off to Massachusetts to preach the Word if the Puritans decided once again to torture Quakers for their beliefs, etc. Woolman interpreted this literally. He spent his teenage years being like “I am depraved, I am evil, I have not once provoked anyone into whipping me to death, I don’t even want to be whipped to death.”

As a teenager, Woolman fell in with a bad crowd and committed some sins. What kind of sins? I don’t know. Sins. He's not telling us:

“I hastened toward destruction,” he writes. “While I meditate on the gulf toward which I travelled … I weep; mine eye runneth down with water.”

In actuality, Woolman’s corrupting friends were all... Quakers who happened to be somewhat less strict than he was. We have his friends' diaries and none of them remarked on any particular sins committed in this period. Biographers have speculated that Woolman was part of a book group and perhaps the great sin he was reproaching himself for was reading nonreligious books. He may also have been reproaching himself for swimming, skating, riding in sleighs, or drinking tea.

Woolman is so batshit about his teenage wrongdoing that many readers have speculated about the existence of different, non-Quaker friends who were doing all the sins. However, we have no historical evidence of him having other friends, and we have a fuckton of historical evidence of Woolman being extremely hard on himself about minor failings (or “failings”).

Most people who are Like That as teenagers grow out of it. Woolman didn’t. He once said something dumb in Weekly Meeting1 and then spent three weeks in a severe depression about it. He never listened to nonreligious music, read fiction or newspapers, or went to plays. He once stormed down to a tavern to tell the tavern owner that celebrating Christmas was sinful.

... if Woolman were just an 18th century neurotic, no one would remember him. We care about him because of his attitude about slavery.

When Woolman was 21, his employer asked him to write a bill of sale for an enslaved woman. Woolman knew it was wrong. But his employer told him to and he was scared of being fired. Both Woolman’s employer and the purchaser were Quakers themselves, so surely if they were okay with it it was okay. Woolman told both his master and the purchaser that he thought that Christians shouldn't own enslaved people, but he wrote the bill.

After he wrote the bill of sale Woolman lost his inner peace and never really recovered it. He spent the rest of his life struggling with guilt and self-hatred. He saw himself as selfish and morally deficient. ...

Woolman worked enough to support himself, but the primary project of his life was ending slavery. He wrote pamphlet after pamphlet making the case that slavery was morally wrong and unbiblical. He traveled across America making speeches to Quaker Meetings urging them to oppose slavery. He talked individually with slaveowners, both Quaker and not, which many people criticized him for; it was “singular”, and singular was not okay. ...

It is difficult to overstate how much John Woolman hated doing anti-slavery activism. For the last decade of his life, in which he did most of his anti-slavery activities, he was clearly severely depressed. ... Partially, he hated the process of traveling: the harshness of life on the road; being away from his family; the risk of bringing home smallpox, which terrified him.

But mostly it was the task being asked of Woolman that filled him with grief. Woolman was naturally "gentle, self-deprecating, and humble in his address", but he felt called to harshly condemn slaveowning Quakers. All he wanted was to be able to have friendly conversations with people who were nice to him. But instead, he felt, God had called him to be an Old Testament prophet, thundering about God’s judgment and the need for repentance. ...

Woolman craved approval from other Quakers. But even Quakers personally opposed to slavery often thought that Woolman was making too big a deal about it. There were other important issues. Woolman should chill. His singleminded focus on ending slavery was singular, and being singular was prideful. Isn’t the real sin how different Woolman’s abolitionism made him from everyone else?

Sometimes he persuaded individual people to free their slaves, but successes were few and far between. Mostly, he gave speeches and wrote pamphlets as eloquently as he could, and then his audience went “huh, food for thought” and went home and beat the people they’d enslaved. Nothing he did had any discernible effect.

... Woolman spent much of his time feeling like a failure. If he were better, if he followed God’s will more closely, if he were kinder and more persuasive and more self-sacrificing, then maybe someone would have lived free who now would die a slave, because Woolman wasn’t good enough.

The modern version of this is probably what Thomas Kwa wrote about here:

I think that many people new to EA have heard that multipliers like these exist, but don't really internalize that all of these multipliers stack multiplicatively. ... If she misses one of these multipliers, say the last one, ... Ana is losing out on 90% of her potential impact, consigning literally millions of chickens to an existence worse than death. To get more than 50% of her maximum possible impact, Ana must hit every single multiplier. This is one way that reality is unforgiving.

From one perspective, Woolman was too hard on himself about his relatively tangential connection to slavery. From another perspective, he is one of a tiny number of people in the eighteenth century who has a remotely reasonable response to causing a person to be in bondage when they could have been free. Everyone else flinched away from the scale of the suffering they caused; Woolman looked at it straight. Everyone else thought of slaves as property; Woolman alone understood they were people.

Some people’s high moral standards might result in unproductive self-flagellation and the refusal to take actions because they might do something wrong. But Woolman derived strength and determination from his high moral standards. When he failed, he regretted his actions and did his best to change them. At night he might beg God to fucking call someone else, but the next morning he picked up his walking stick and kept going.

And the thing he was doing mattered. Quaker abolitionism wasn’t inevitable; it was the result of hard work by specific people, of whom Woolman was one of the most prominent. If Woolman were less hard on himself, many hundreds if not thousands of free people would instead have been owned things that could beaten or raped or murdered with as little consequence as I experience from breaking a laptop.

An aside (doubling as warning) on mission orientation, quoting Tanner Greer's Questing for Transcendence:

... out of the lands I’ve lived and roles I’ve have donned, none blaze in my memory like the two years I spent as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ. It is a shame that few who review my resume ask about that time; more interesting experiences were packed into those few mission years than in the rest of the lot combined. ... I doubt I shall ever experience anything like it again. I cannot value its worth. I learned more of humanity’s crooked timbers in the two years I lived as missionary than in all the years before and all the years since.

Attempting to communicate what missionary life is like to those who have not experienced it themselves is difficult. ... Yet there is one segment of society that seems to get it. In the years since my service, I have been surprised to find that the one group of people who consistently understands my experience are soldiers. In many ways a Mormon missionary is asked to live something like a soldier... [they] spend years doing a job which is not so much a job as it is an all-encompassing way of life.

The last point is the one most salient to this essay. It is part of the reason both many ex-missionaries (known as “RMs” or “Return Missionaries” in Mormon lingo) and many veterans have such trouble adapting to life when they return to their homes. ... Many RMs report a sense of loss and aimlessness upon returning to “the real world.” They suddenly find themselves in a society that is disgustingly self-centered, a world where there is nothing to sacrifice or plan for except one’s own advancement. For the past two years there was a purpose behind everything they did, a purpose whose scope far transcended their individual concerns. They had given everything—“heart, might, mind and strength“—to this work, and now they are expected to go back to racking up rewards points on their credit card? How could they?

The soldier understands this question. He understands how strange and wonderful life can be when every decision is imbued with terrible meaning. Things which have no particular valence in the civilian sphere are a matter of life or death for the soldier. Mundane aspects of mundane jobs (say, those of the former vehicle mechanic) take on special meaning. A direct line can be drawn between everything he does—laying out a sandbag, turning off a light, operating a radio—and the ability of his team to accomplish their mission. Choice of food, training, and exercise before combat can make the difference between the life and death of a soldier’s comrades in combat. For good or for ill, it is through small decisions like these that great things come to pass.

In this sense the life of the soldier is not really his own. His decisions ripple. His mistakes multiply. The mission demands strict attention to things that are of no consequence in normal life. So much depends on him, yet so little is for him.

This sounds like a burden. In some ways it is. But in other ways it is a gift. Now, and for as long as he is part of the force, even his smallest actions have a significance he could never otherwise hope for. He does not live a normal life. He lives with power and purpose—that rare power and purpose given only to those whose lives are not their own.

... It is an exhilarating way to live.

This sort of life is not restricted to soldiers and missionaries. Terrorists obviously experience a similar sort of commitment. So do dissidents, revolutionaries, reformers, abolitionists, and so forth. What matters here is conviction and cause. If the cause is great enough, and the need for service so pressing, then many of the other things—obedience, discipline, exhaustion, consecration, hierarchy, and separation from ordinary life—soon follow. It is no accident that great transformations in history are sprung from groups of people living in just this way. Humanity is both at its most heroic and its most horrifying when questing for transcendence.

Appreciate the pointer to that post! That's basically the sort of thing I'm looking for (more reading material for 'gears'). And thanks again for writing the main post.

Great post, thank you for writing it. I particularly appreciate the sketch of your causal model summarizing the evidence for the relationships between growth, liberal democracy, human capital, peace, and x-risk; I think you deconfused me quite a bit w.r.t "the world getting better" with that.

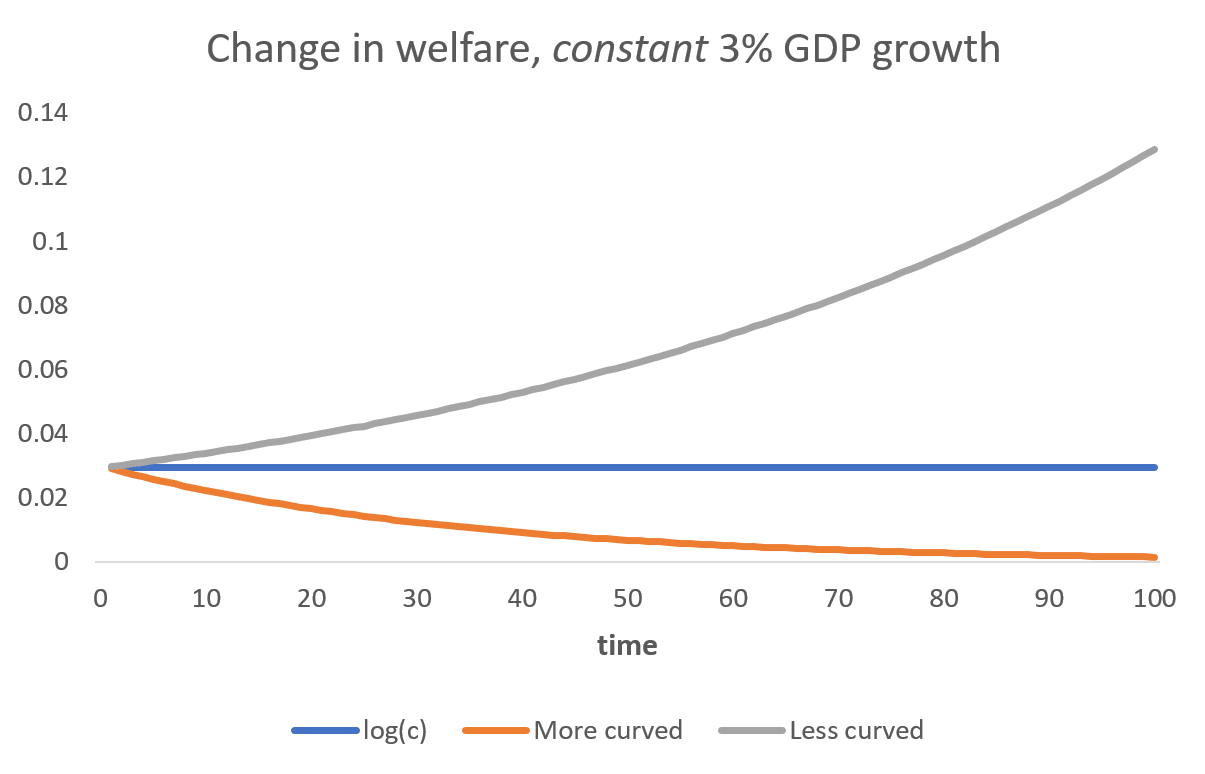

But even if GDP percentage growth slows, wellbeing growth can still speed up, for two reasons:

- The dollar GDP/capita growth rate goes up. Even if we adjust for inflation, Americans had ~$600 more every year in the 60s, but now have ~$900 more per year in the 2010s.[65]

At first blush this seemed wrong, since I tend to assume log utility to simplify modeling. Your footnote linking to Basil Halperin's essay does note that this assumption is in fact an assumption, and that if utility is in fact "less curved" than log we can still have wellbeing growth speedup with GDP % growth slowdown (this was probably obvious to you but isn't clarified in the text):

But Halperin's essay doesn't actually explore whether this "less curved than log" assumption is true. Do you happen to know of empirical evidence for it?

The only reference I've come across provides evidence against it – it's this section in Sam Nolan's Quantifying Uncertainty in GiveWell's GiveDirectly Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Quote:

Isoelastic vs Logarithmic increases in consumption

GiveWell measures GiveDirectly's cost-effectiveness by doublings of consumption per year. For instance, Increasing an individual's consumption from $285.92 to $571.84 for a year would be considered 1 unit of utility.

However, there is a bit of ambiguity here. What happens when you double someone's consumption twice? For instance, $285.92 to $1,143.68 a year? So, if increasing consumption by 100% has a utility of 1, how much utility does this have? A natural answer might be that doubling twice creates two units of utility. This answer is what the GiveWell CEA currently assumes. This assumption is implicit by representing utility as logarithmic increases in consumption.

However, how much people prefer the first double of consumption over the second is an empirical question. And empirically, people get more utility from the first doubling of consumption than the second. Doubling twice creates 1.66 units rather than 2. An isoelastic utility function can represent this difference in preferences.

Isoelastic utility functions allow you to specify how much one would prefer the first double to the second with the parameter. When , the recipient values the first double the same as the second and is what the current CEA assumes. When , recipients prefer the first doubling in consumption as worth more than the second. Empirically, . GiveWell recognises this and uses in their calculation of the discount rate:

Increases in consumption over time meaning marginal increases in consumption in the future are less valuable. We chose a rate of 1.7% based on an expectation that economic consumption would grow at 3% each year, and the function through which consumption translates to welfare is isoelastic with eta=1.59. (Note that this discount rate should be applied to increases in ln(consumption), rather than increases in absolute consumption; see calculations here)

I've created a desmos calculator to explore this concept. From the calculator, you can change the value of and see how isoelastic utility compares to logarithmic utility.

GiveDirectly transfers don't usually double someone's consumption for a year but increase it by a lower factor. So an isoelastic utility would find that recipients would gain more utility than logarithmic utility implies.

Changing from 1 to 1.59 increases GiveDirectly's cost-effectiveness by 11%. Reducing the cost of doubling someone's consumption for a year from $466.34 to $415.87.

To be clear, I don't know anything else about this topic; I was just surprised/skeptical to see the wellbeing growth speedup point.

Edited to add: I was trivially wrong, sorry, I misread Sam's post. Quoting the relevant section from the passage above:

When , recipients prefer the first doubling in consumption as worth more than the second. Empirically, . GiveWell recognises this and uses in their calculation of the discount rate

So this is evidence for your point, not against.

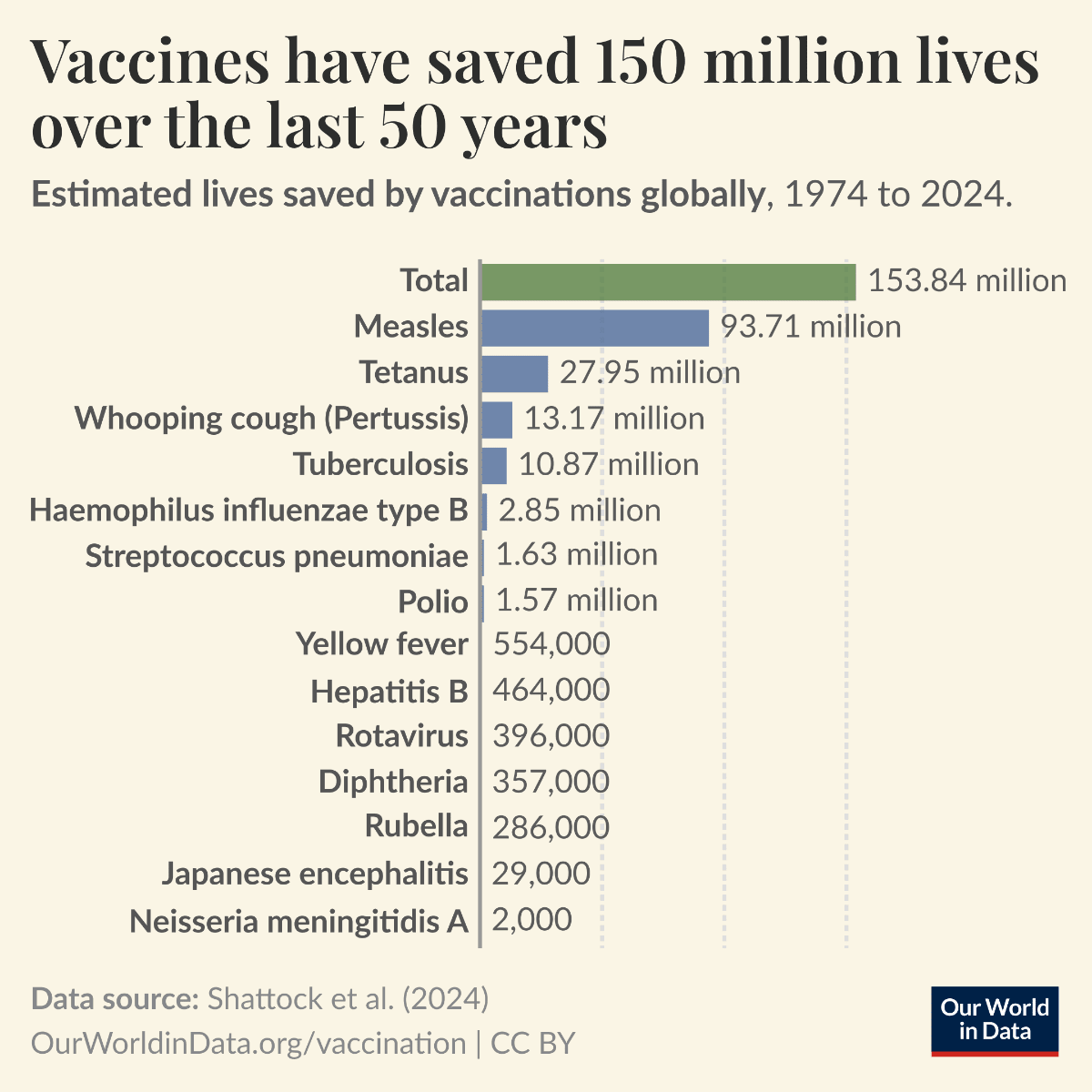

This WHO press release was a good reminder of the power of immunization – a new study forthcoming publication in The Lancet reports that (liberally quoting / paraphrasing the release)

- global immunization efforts have saved an estimated 154 million lives over the past 50 years, 146 million of them children under 5 and 101 million of them infants

- for each life saved through immunization, an average of 66 years of full health were gained – with a total of 10.2 billion full health years gained over the five decades

- measles vaccination accounted for 60% of the lives saved due to immunization, and will likely remain the top contributor in the future

- vaccination against 14 diseases has directly contributed to reducing infant deaths by 40% globally, and by more than 50% in the African Region

- the 14 diseases: diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type B, hepatitis B, Japanese encephalitis, measles, meningitis A, pertussis, invasive pneumococcal disease, polio, rotavirus, rubella, tetanus, tuberculosis, and yellow fever

- fewer than 5% of infants globally had access to routine immunization when the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was launched 50 years ago in 1974 by the World Health Assembly; today 84% of infants are protected with 3 doses of the vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) – the global marker for immunization coverage

- there's still a lot to be done – for instance, 67 million children missed out on one or more vaccines during the pandemic years

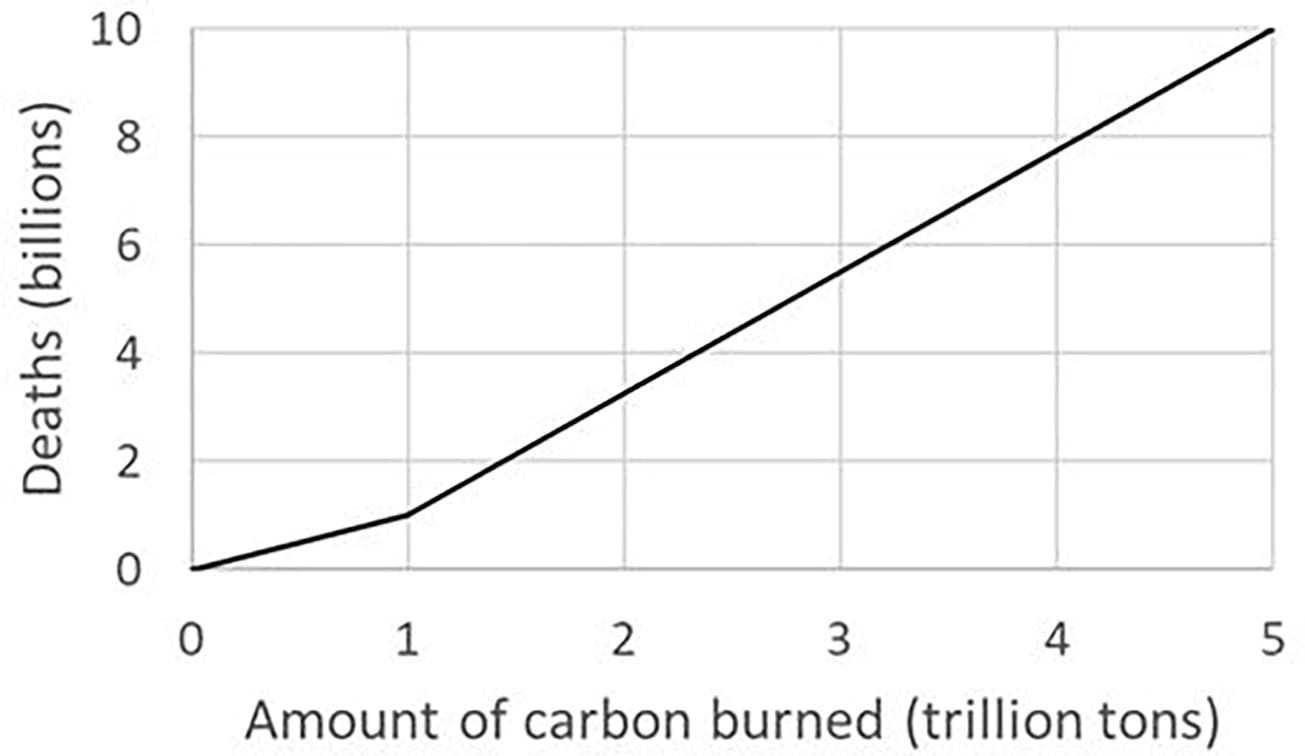

The 1,000-ton rule is Richard Parncutt's suggestion for reframing the political message of the severity of global warming in particularly vivid human rights terms; it says that someone in the next century or two is prematurely killed every time humanity burns 1,000 tons of carbon.

I came across this paper while (in the spirit of Nuno's suggestion) trying to figure out the 'moral cost of climate change' so to speak, driven by my annoyance that e.g. climate charity BOTECs reported $ per ton of CO2-eq averted in contrast to (say) the $ per death averted bottomline of GHW charities, since I don't intrinsically care to avert CO2-equivalent emissions the way I do about averting deaths. (To be clear, I understand why the BOTECs do so and would do the same for work; this is for my own moral clarity.)

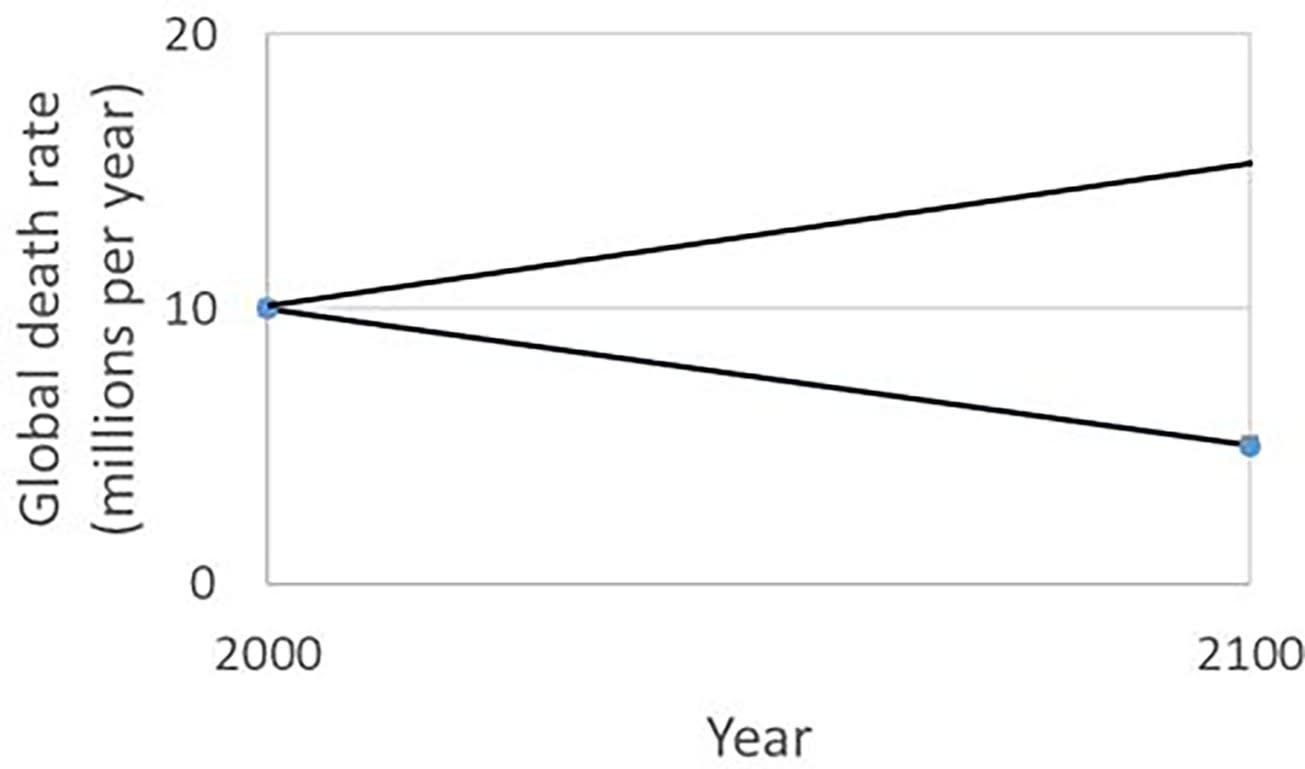

Parncutt's derivation is simple: burning a trillion tons of carbon will cause ~2 °C of anthropogenic global warming, which will in turn cause 1 - 10 million premature deaths a year "for a period of several centuries", something like this:

The lower line represents deaths due to poverty without AGW. As the negative effect of AGW overtakes the positive effect of development, the death rate will increase, as shown by the upper line. In a more accurate model, the upper line might be concave upward on the left (exponential increase) and concave downward on the right (approaching a peak).

Based on the 1,000-ton rule, Pearce & Parncutt suggest the 'millilife' as "an accessible unit of measure for carbon footprints that is easy to understand and may be used to set energy policy to help accelerate carbon emissions reductions". A millilife is a measure of intrinsic value defined to be 1/1000th of a human life; the 1,000-ton rule says that burning a ton of fossil carbon destroys a millilife. This lets Pearce & Parncutt make statements like these, at an individual level (all emphasis mine):

For example in Canada, which has some of the highest yearly carbon emissions per capita in the world at around 19 tons of CO2 or 5 tons of carbon per person, roughly 5 millilives are sacrificed by an average person each year. As the average Canadian lives to be about 80, he/she sacrifices about 400 millilives (0.4 human lives) in the course of his/her lifetime, in exchange for a carbon-intensive lifestyle

and

... an average future AGW-victim in a developing country will lose half of a lifetime or 30–40 life-years, as most victims will be either very young or very old. If the average climate victim loses 35 life-years (or 13,000 life-days), a millilife corresponds to 13 days.

Stated in another way: if a person is responsible for burning a ton of fossil carbon by flying to another continent and back, they effectively steal 13 days from the life of a future poor person living in the developing world. If the traveler takes 1000 such trips, they are responsible for the death of a future person.

and for "large-scale energy decisions":

... the Adani Carmichael coalmine in Queensland, Australia, is currently under construction and producing coal since 2021. Despite massive protests over several years, it will be the biggest coalmine ever. Its reserves are up to 4 billion tons of coal, or 3 billion tons of carbon. If all of that was burned, the 1000-tonne rule says it would cause the premature deaths of 3 million future people. Given that the 1000-tonne rule is only an order-of-magnitude estimate, the number of caused deaths will lie between one million and 10 million. ... Many of those who will die are already living as children in the Global South; burning Carmichael coal will cause their future deaths with a high probability. Should energy policy allow that to occur?

Pearce & Parncutt then use the 1,000-ton rule and millilife to make various suggestions. Here's one:

Under what circumstances might a government ban or outlaw an entire corporation or industry, considered a legal entity or person—for example, the entire global coal industry? ...

Ideally, a company should not cause any human deaths at all. If it does, those deaths should be justifiable in terms of improvements to the quality of life of others. For example, a company that builds a bridge might reasonably risk a future collapse that would kill 100 people with a probability of 1%. In that case, the company accepts that on average one future person will be killed as a result of the construction of the bridge. It may be reasonable to claim that the improved quality of life for thousands or millions of people who cross the bridge justifies the human cost.

Fossil fuel industries are causing far more future deaths than that, raising the question of the point at which the law should intervene. As a first step to solving this problem, it has been proposed a rather high threshold (generous toward the corporations) is appropriate. A company does not have the right to exist if its net impact on human life (e.g., a company/industry might make products that save lives like medicine but do kill a small fraction of users) is such that it kills more people than it employs. This requirement for a company’s existence is thus:

Number of future premature deaths/year < Number of full-time employees (1)

This criterion can be applied to an entire industry. If the industry kills more people than it employs, then primary rights (life) are being sacrificed for secondary rights (jobs or profits) and the net benefit to humankind is negative. If an industry is not able to satisfy Equation (1), it should be closed down by the government.

... the coal industry kills people by polluting the air that they breathe. ... In the U.S., about 52,000 human lives are sacrificed per year to provide coal-fired electricity. ... In the U.S., coal employed 51,795 people in 2016. Since the number of people killed is greater than the number employed, the U.S. coal industry does not satisfy Equation (1) and should be closed down. This conservative conclusion does not include future deaths caused by climate change due to burning coal.

One more energy policy suggestion (there's many more in the paper):

Applying asset forfeiture laws (also referred to as asset seizure) to manslaughter caused by AGW. These laws enable the confiscation of assets by the U.S. government as a type of criminal-justice financial obligation that applies to the proceeds of crime. Essentially, if criminals profit from the results of unlawful activity, the profits (assets) are confiscated by the authorities.

This is not only a law in the U.S. but is in place throughout the world. For example, in Canada, Part XII.2 of the Criminal Code, provides a national forfeiture régime for property arising from the commission of indictable offenses. Similarly, ‘Son of Sam laws’ could also apply to carbon emissions. In the U.S., Son of Sam laws refer to laws designed to keep criminals from profiting from the notoriety of their crimes and often authorize the state to seize funds earned by the criminals to be used to compensate the criminal’s victims.

If that logic of asset forfeiture is applied to fossil fuel company investors who profit from carbon-emission-related manslaughter, taxes could be set on fossil fuel profits, dividends, and capital gains at 100% and the resultant tax revenue could be used for energy efficiency and renewable energy projects or to help shield the poor from the most severe impacts of AGW. ...

Such AGW-focused asset forfeiture laws would also apply to fossil fuel company executive compensation packages. Energy policy research has shown that it is possible to align energy executive compensation with careful calibration of incentive equations such that the harmful effects of emissions can be prevented through incentive pay. Executives who were compensated without these safeguards in place would have their incomes seized the same as other criminals benefiting materially from manslaughter.

I have no (defensible) opinion on these suggestions; curious to know what anyone thinks.

Yeah rising inequality is a good guess, thank you – the OWID chart also shows the US experiencing the same trajectory direction as India (declining average LS despite rising GDP per capita). I suppose one way to test this hypothesis is to see if China had inequality rise significantly as well in the 2011-23 period, since it had the expected LS-and-GDP-trending-up trajectory. Probably a weak test due to potential confounders...

This sounds similar to what David Chapman wrote about in How to think real good; he's mostly talking about solving technical STEM-y research problems, but I think the takeaways apply more broadly:

(sorry for the overly long quote, concision is a work in progress for me...)