Stanford EA holds weekly discussion-focused meetings, with an average turnout of around 15 people. These are based around sheets with a list of questions and relevant background; you can see examples of previous ones here. (Thanks to Kelsey Piper for writing these!) At one point we planned to consistently provide a page of background on the other side of the sheet; we've partially stopped doing so, as the background didn't seem to really guide the conversation.

First we have a few minutes to write down our answers to the questions on the sheet. We then go around the circle doing introductions, as specified at the top of the sheet. Then, for each question, we go around the circle and give our response to it.

Most of the interesting discussion happens as prompted by things people say when providing their answers. It’s pretty loose: people ask you about your answer, and you respond to them, and the discussion kind of goes where it will. When it’s gone on a long enough tangent, Kelsey moves the conversation along by asking the next person to give their answer to the question. This is a great way of ensuring that the conversation can stay roughly on track and everyone gets a chance to speak. Often meetups have a problem where new people don’t know what to say; this goes some of the way to solving that.

These questionnaires also make the discussion more accessible to people who know less about effective altruism, because often it’s easy to grasp the complex natures of questions like “how much do you value IQ increases vs saving more lives”. The Stanford EA meetup, like all meetups, occasionally veers pretty hard into jargon and confusing advanced territory, but Kelsey is able to somewhat restrain that by moving the conversation to the next person or next question. The background info on the sheets, when present, also helps.

It’s rare that we actually make it all the way through the questions. Usually we discuss some aspects of a later question when talking about an earlier one, or we do a quick straw poll about a later one and don’t discuss it further. Generally, the topics which lead to the most digressions are the more abstract or philosophical ones; when we talked about population ethics, we spent an hour and a half discussing the first question.

The meetup lasts for an hour and a half, after which most of us get dinner together. Dinner discussions tend to still be about EA topics, but instead about anything people who want to talk about. They also tend to be where we discuss/plan ideas for non-discussion meetings; the larger number of people allows the leaders to get better feedback on which future events should be run.

(Thanks to Buck Shlegeris for writing the first draft of this post; thanks to Kelsey for running the meetups and writing the discussion sheets; thanks to Alex Richard for revisions.)

15

0

0

Reactions

0

0

Curated and popular this week

Paul Present

+ 0 more

·

Note: I am not a malaria expert. This is my best-faith attempt at answering a question that was bothering me, but this field is a large and complex field, and I’ve almost certainly misunderstood something somewhere along the way.

Summary

While the world made incredible progress in reducing malaria cases from 2000 to 2015, the past 10 years have seen malaria cases stop declining and start rising. I investigated potential reasons behind this increase through reading the existing literature and looking at publicly available data, and I identified three key factors explaining the rise:

1. Population Growth: Africa's population has increased by approximately 75% since 2000. This alone explains most of the increase in absolute case numbers, while cases per capita have remained relatively flat since 2015.

2. Stagnant Funding: After rapid growth starting in 2000, funding for malaria prevention plateaued around 2010.

3. Insecticide Resistance: Mosquitoes have become increasingly resistant to the insecticides used in bednets over the past 20 years. This has made older models of bednets less effective, although they still have some effect. Newer models of bednets developed in response to insecticide resistance are more effective but still not widely deployed.

I very crudely estimate that without any of these factors, there would be 55% fewer malaria cases in the world than what we see today. I think all three of these factors are roughly equally important in explaining the difference.

Alternative explanations like removal of PFAS, climate change, or invasive mosquito species don't appear to be major contributors.

Overall this investigation made me more convinced that bednets are an effective global health intervention.

Introduction

In 2015, malaria rates were down, and EAs were celebrating. Giving What We Can posted this incredible gif showing the decrease in malaria cases across Africa since 2000:

Giving What We Can said that

> The reduction in malaria has be

LewisBollard

+ 0 more

·

> How the dismal science can help us end the dismal treatment of farm animals

By Martin Gould

----------------------------------------

Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

----------------------------------------

This year we’ll be sharing a few notes from my colleagues on their areas of expertise. The first is from Martin. I’ll be back next month. - Lewis

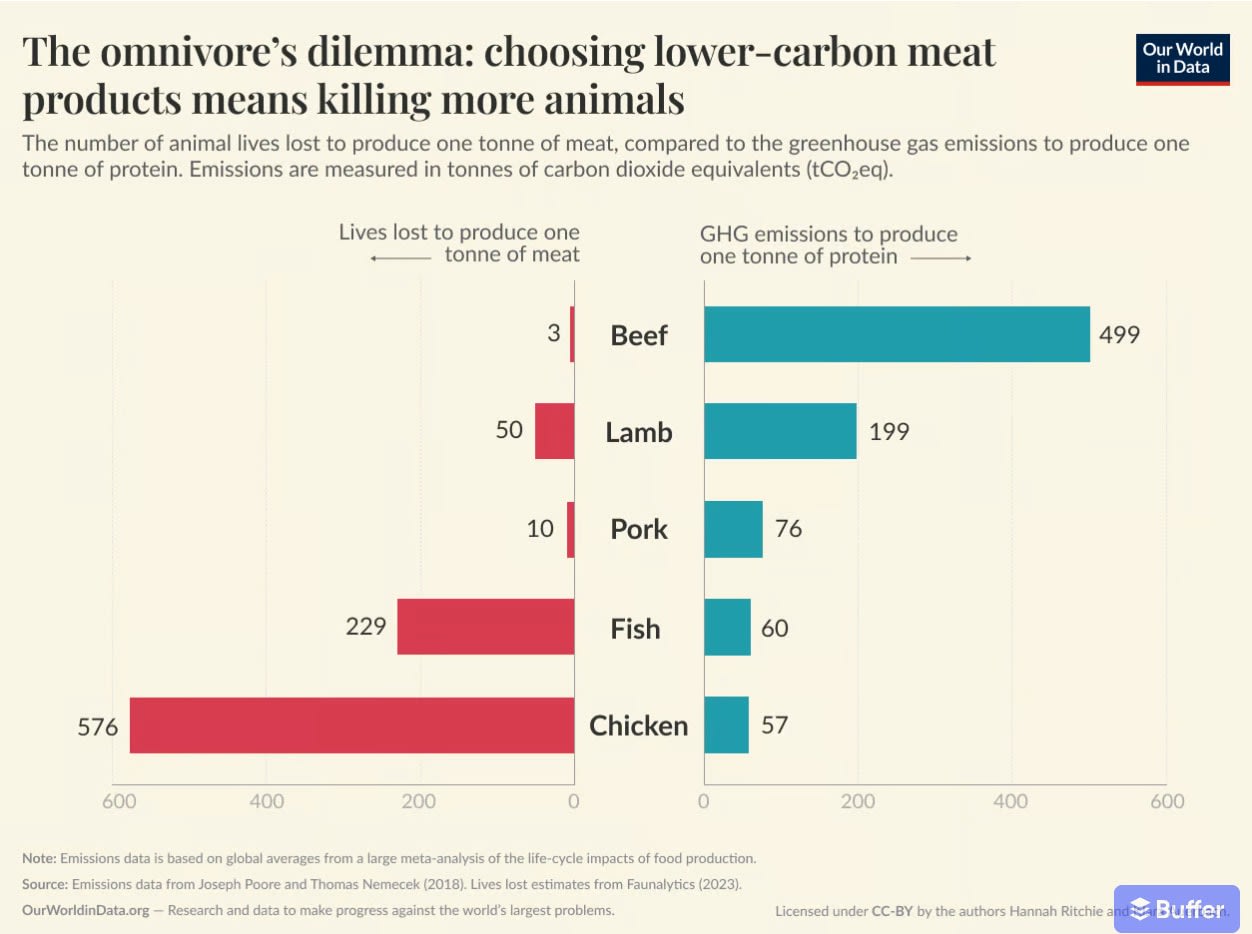

In 2024, Denmark announced plans to introduce the world’s first carbon tax on cow, sheep, and pig farming. Climate advocates celebrated, but animal advocates should be much more cautious. When Denmark’s Aarhus municipality tested a similar tax in 2022, beef purchases dropped by 40% while demand for chicken and pork increased.

Beef is the most emissions-intensive meat, so carbon taxes hit it hardest — and Denmark’s policies don’t even cover chicken or fish. When the price of beef rises, consumers mostly shift to other meats like chicken. And replacing beef with chicken means more animals suffer in worse conditions — about 190 chickens are needed to match the meat from one cow, and chickens are raised in much worse conditions.

It may be possible to design carbon taxes which avoid this outcome; a recent paper argues that a broad carbon tax would reduce all meat production (although it omits impacts on egg or dairy production). But with cows ten times more emissions-intensive than chicken per kilogram of meat, other governments may follow Denmark’s lead — focusing taxes on the highest emitters while ignoring the welfare implications.

Beef is easily the most emissions-intensive meat, but also requires the fewest animals for a given amount. The graph shows climate emissions per tonne of meat on the right-hand side, and the number of animals needed to produce a kilogram of meat on the left. The fish “lives lost” number varies significantly by

Recent opportunities in Building effective altruism

24

This is super practical advice that I can definitely see myself applying in the future. The introductions on the sheets seem particularly well-suited to getting people engaged.

Also, "What is the first thing you would do if appointed dictator of the United States?" likely just entered my favorite questions to ask anyone in ice-breaker scenarios, many of which have nothing to do with EA.

The question we've had the most success with for a regular/weekly meetup is "what is something interesting you've learned/read/thought about recently". The advantage to keeping it consistent is that people know what to expect; this question also avoids most of the disadvantages of keeping the question consistent (namely that people repeat themselves and get bored). It also tends to provoke fascinating answers.

I can also vouch for the success of "What's one good thing and one bad thing that has happened to you this week/month/since last time?" Each person picks one of each and talks about it. Naturally, some people may bring up things related to EA very easily with this question if they are involved with it.